Blog

Welcome to the Busybird blog, where you can find helpful articles, updates, industry news and more. Make sure you stay up to date by signing up to our newsletter below.

Editing Attitudes to Live By

February 8, 2018 In our last blog, we offered a 10-step process for revision if you were a writer.

In our last blog, we offered a 10-step process for revision if you were a writer.

In this blog, we’re going to take a look at it from the other side – if you’re an editor or providing feedback in a workshop group.

Now many of the last blog’s rules can still apply if you’re editing or providing feedback. What’s distinctly different here are the attitudes you need to keep in mind.

1. Recognise What the Author’s Trying to Accomplish

It’s amazing the amount of authors and feedbackers who try to take a piece in the direction they think it needs to go. Sure, sometimes an author might be unclear on what their story’s about. A manuscript that was initially about adultery might twist into a story about a character’s emotional and intellectual growth.

It’s times like this when the editor needs to gently challenge the author with a simple question: What do you think your story is about? This can be enlightening for authors – a question they’ve never asked themselves because they’ve been too immersed in the material to see objectively.

Once they understand (or realise) what the story’s actually about, the editor or feedbacker should help them try to get to that destination, rather than take them somewhere they don’t want to go, are unwilling to go, or never intended to go.

What an editor/feedbacker should never, ever do is make an assumption, or conclude what a piece is (or should be) about because that is going to prejudice their feedback, and possibly take the author further and further from their vision. It’s also going to cause friction between the editor/feedbacker and the author.

What often ultimately happens is that instead of getting an author’s vision, or even the editor’s vision, you get this murky neither here nor there vision.

2. Do Not Edit by Committee

This applies particularly to workshopping groups. Five people might’ve read a piece, and then a few of them might start commenting on what they believe the piece needs. Their comments stimulate other conversation. Somebody who’s been silent to this point might feel they need to agree. Somebody else might think they need to say something for the sake of saying something. If you have somebody particularly dominant and/or influential providing feedback, others might unwittingly support them to curry favour, or so they’re seen to be contributing, even if they don’t particularly believe in what they’re saying.

Often, as a group they begin brainstorming as if this was their idea. This process works in a television writer’s room where a group of writers try to map out a television series and every possibility has to be exhausted, but in this situation the showrunner (the writer in charge) still has the overarching vision. Everybody is working towards that vision. When they stray, the showrunnner will herd them back into line.

The collective often doesn’t work for stories or books. Instead of trying to fulfill the author’s vision, or even their own individual vision (which they shouldn’t be doing – see the previous point), they create this bastardised hodgepodge vision that doesn’t belong to anybody.

3. Honour the Writer’s Voice

Lots of editors and feedbackers are writers themselves. Unfortunately, this means that too many editors and feedbackers go into an author’s piece as if it were their own, and begin revising and commenting according to what they would do had this been a piece they’d written.

The author might use short, punchy sentences, whereas the editor/feedbacker might prefer if the sentences were longer. They might create unnecessary linkages. Etc. They rewrite passages. Or make suggestions in accordance with what they would do, rather than what the author would do.

This isn’t editing. This isn’t providing feedback. This is ghostwriting.

Honour the writer’s voice. Honour their style. Obviously, there are grammatical and punctuation rules that need to be observed but it’s imperative to find the author’s wavelength and keep their work sounding uniquely like them.

4. Do Not Be Afraid of White Space

Way too many editors and feedbackers panic if they’ve gone some distance – like a page – and haven’t made a comment. That unblemished margin intimidates them. They feel they need to comment just to prove they’re doing their job.

It might simply be that the content doesn’t need commenting. Yes, this happens! Something can be just fine.

Don’t fear white space in a margin.

5. Don’t Let Your Reputation Get to Your Head

Some editors and feedbackers may have a reputation they feel they need to live up to, e.g. from my own experience, I had a reputation for slashing verbosity, and for a little period there felt I needed to slash – whether the text deserved it or not – to justify my reputation. But then I learned – just as with the white space – it’s okay to not do anything.

This is an extremely difficult thing for lots of editors and feedbackers. They’re not reading a piece for recreation. They’re going into it with the intent of editing and commenting, so feel they need to regardless.

Remember – and not just in relation to this point, but editing and providing feedback overall – sometimes, things are fine just as they are.

These are the attitudes to keep in mind while editing or feedbacking. They’re attitudes you should live by.

An author’s work – even if that work is ridiculously flawed – is sacred. The work not only represents the author, it is the author.

Be respectful, if not reverential, and help the author get to where they want to go.

A 10-Step Process for Revision

January 25, 2018 How do you approach revision? Do you just sit down and trust your instincts? Do you just let whatever happens happen? The chances are if you have a haphazard approach, you’ll have haphazard results.

How do you approach revision? Do you just sit down and trust your instincts? Do you just let whatever happens happen? The chances are if you have a haphazard approach, you’ll have haphazard results.

When revising, you should have a plan. You should have a methodical approach that’ll cover all the requirements of the revision.

Here’s the ten-step process I use …

10. Read Your Work Until You’re Sick of It

If you think that first draft is great, you’re kidding yourself. The first draft is a spill. This is where you just need to get everything out. It might contain the potential for greatness, but it’s going to need work.

Read it, reread it, and keep doing that until you can get no more out of it.

9. Put Your Work Away for a Period

Sometimes, deadlines don’t allow us this leeway. But, if you can, put your work away – for a minimum of one week, but for as long as three months (or longer) if possible.

When you finally go back to it, it should be with a fresh perspective. You might’ve even come up with a few new ideas during the interim. Often, stepping away from your work – and removing that pressure to produce – frees your imagination.

8. Start Reading and Rereading Again

Attack your work with a new vigour. If you’ve given yourself enough time, it’ll be like reading something for the first time. This’ll help with your objectivity.

7. Send It Out to Alpha Readers

Develop a network of like-minded people with whom you share your work and exchange feedback. Make sure they’re people you respect, and who understand what you’re trying to do. They don’t have to be writing the same genre as you to provide good feedback. But do be conscious of people who specialize in a certain genre, and read everything through the filter of that genre, e.g. they only read romance, and expect everything else they read to be written the same as romance would be written.

6. The Feedback Revision

You should now have some feedback to focus on. Get back to revising. Address every point. Even if you don’t agree with feedback, consider why that feedback was offered. Is there something about that particular point you should consider, even if it’s a different facet of it? If more than one person has given you the same feedback, then it’s probably valid.

5. The Double Read

Read a chapter, then read it again. The first read is just to familiarize yourself with everything and where it’s all heading, and the second time is to address it with that familiarity fresh in your mind. Just because you’re the author doesn’t mean you’re going to remember every line you’ve written. This double-reading technique imprints the prose on your mind on the first pass so that you can revise with abandon on the second.

Finally, don’t do too much daily – only about twenty or pages or so (which will actually amount to forty pages or so when you read everything twice). The mind tires easily, so it’s best to stagger the digestion of the material.

4. The Red Edit – Structure

Change the colour of the font to red. This forces the brain to process the information differently. If possible, change the font also. Examine how your writing works as a whole. Does it make sense? Are you delivering your information in the best way to communicate your message? Are your characters layered? Are they necessary? Are there areas that are overwritten which could be more succinct? Etc. Be merciless. Test your writing’s defenses and exploit it’s weak spots. If, at any time, your response to a query is, I think it’s okay, then it’s likely it’s not okay.

As with the double read, try not to do too much daily.

3. The Blue Edit – Copy

Now change the colour of the font to blue. Again, if possible change the font to something else.

Focus now on the copy, correcting grammar, and punctuation. Examine your writing line by line. is it clear? Is there a better way to say things?

Importantly, give yourself lots of breaks as you’re doing this. It’s very easy to slip into reading your writing without registering anything.

2. The Normal Read

Return the font to whatever colour and type you’d normally use. Sit down and read your book as if you had picked it up to read recreationally. Whereas in previous steps, you would’ve read only a small, set amount daily, now read it in big clumps to see if the flow works. The pacing is something that’s hard to judge when you’re deeply immersed in the copy itself.

1. Run a Spellcheck

Even if your spelling is brilliant, run a spellcheck. Often, spelling errors are a result of mistyping, rather than not knowing how to spell.

If you’re using Word, turn off the grammar checker. The grammar checker can, unwittingly, introduce errors. if you have a fine understanding of grammar and can recognize when this is happening, great, but if not, it’s best to proceed without it.

Does this seem like a lot of work?

It is – but writing is. People who believe they can vomit out a first draft and give it one quick read and revision before sending it out are deluding themselves.

Writing is a lot of hard work.

Don’t ever believe otherwise.

Making It

December 7, 2017 There’s always been a romanticism attached to writing – the thought of sitting up endless nights, pounding away at the keyboard, telling a story only you can tell. Many inexperienced writers visualize themselves as the next Hemmingway, Fitzgerald, King, Picoult, or Rowling. But there’s something these writers – and others like them – have in common.

There’s always been a romanticism attached to writing – the thought of sitting up endless nights, pounding away at the keyboard, telling a story only you can tell. Many inexperienced writers visualize themselves as the next Hemmingway, Fitzgerald, King, Picoult, or Rowling. But there’s something these writers – and others like them – have in common.

They are at the very top of the writing tree.

Go into a bookstore, and peruse the shelves. How many names do you recognize? How many of those names are globally recognized? How many of those names are writing bestsellers? The answer to all three questions will be surprisingly few. Yet many believe that if you’re writing and being published that you’ll become rich. Uh uh. Think of writing as comparable to the music industry: is every band/artist releasing songs and albums that chart into the top ten? A few will. Most won’t. Some will disappear without a trace.

That’s not to say you can’t make good money from writing (although, in Australia, it’s harder, given our population), but just that it’s unlikely. Most writers will, in fact, have a full time job that pays the bills and puts food on the table. Or they’ll be working part-time to complement whatever money they’re making from writing.

Oh, but you’re sure about what you’re writing. You have a bestseller!

This belief seems almost a rite of passage for inexperienced writers – they envision themselves as a famous, bestselling author, and daydream about topping the New York Times Bestseller List and giving interviews on shows like Oprah.

But you’re sure.

You wouldn’t be the only one.

Firstly, let’s address the belief that you have a bestseller – we’ve talked about this in other blogs, but we’ll touch briefly on it again.

Even if you’ve written a gripping story and your prose is beautiful, why will your book bump other better-known authors from prime positions on bookstore shelves? How are people even going to know that your book exists? They’ll just find out isn’t a legitimate strategy. Even people who’ve hired publicists and engage in saturation marketing aren’t guaranteed success. The truth is that if there was a formula to manufacturing a bestseller, publishers – with all their resources and market knowledge – would be employing it for every book. They’re not. They will have best sellers, but also moderate sellers, as well as books that don’t live up to expectation.

Secondly, those few authors who experience fame and success usually don’t achieve it instantaneously. It’s a journey of perseverance: perseverance in writing, getting books out there, and – no matter how much they’d rather avoid it – marketing themselves. It’s a continuing unglamorous slog in pursuit of something that still may never happen, or – at the very least – not happen to the magnitude the writer is hoping.

Now while this blog may be construed as negative, it’s intended to be a realistic appraisal of the writing industry. As sure as you can be of yourself and your writing, you are still at the whim of a subjective market. Getting into a position where you could be considered to have ‘made it’ requires a lot of hard work and patience – and luck.

That’s not to say you mightn’t be an exception. It happens. But don’t use that attitude to fuel your fantasy. Use it to fuel your endeavor.

And keep working at it.

Filter

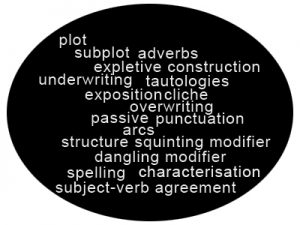

November 23, 2017 As a writer, you write through a filter. That filter shapes every aspect of your writing – not just the creative elements (plot, content, characters, etc.) but also the technical aspects (grammar, spelling, and punctuation, etc.). All the things you don’t know – that can constitute bad writing – exist in this filter and influence how you express yourself.

As a writer, you write through a filter. That filter shapes every aspect of your writing – not just the creative elements (plot, content, characters, etc.) but also the technical aspects (grammar, spelling, and punctuation, etc.). All the things you don’t know – that can constitute bad writing – exist in this filter and influence how you express yourself.

Here’s an example: you don’t know anything about ‘expletive constructions’. What then happens is expletive constructions appear everywhere in your writing. You use them because you don’t know you shouldn’t be using them.

Now you might be wondering, What’s an expletive construction? It’s starting a sentence with something like ‘There was’, ‘There were’, ‘There is’, ‘It was’, etc. E.g. There were three boys sitting at the bus stop could easily read Three boys sat at the bus stop. Expletive constructions commonly sneak into writing. Look back over anything you’ve written. See how often you’ve used them, and if a simple rephrase can eliminate them. I bet you’re surprised.

Once you become aware of an issue – and aware that it is an issue – you’ll be mindful of it. You’ll sit there, writing away, and about to do something just as you’ve done one thousand times before, but then you realise, Uh uh. Can’t do it that way. You rethink. You have to come up with a new way to write this passage – this is great, forcing your mind and imagination to expand, because it’s now transcending a pre-existing boundary.

At first, you might be stumped. It might take you minutes to come up with a new way of writing this sentence. You might scratch your head, get up and pace, sigh in frustration, and even have to take a walk. But, with perseverance, you’ll eventually find your way. The next time it’ll come easier. And then easier again. And so on. Until you’re bolting. No pause exists now.

This is what learning’s about: eradicating as many of these issues as possible. The filter – once this big amorphous glob that encompassed a horde of problems – shrinks. These issues are mostly squeezed out. Mostly. You’ll never wholly eliminate everything. Every writer’s early drafts are going to be flawed, no matter how experienced that writer is. But your early drafts get better. You get better. And you continue to think of new ways to say things.

As a writer, you should always seek to improve your craft. Unlike an athlete, who might have a physical peak, and then decline, a writer can continue to improve – well, at least until they enter their dotage and their mind begins to let them down. But, hopefully, there’s many decades of writing before that happens.

Don’t ever believe you’re as good as you’re going to get. Don’t believe you have no room for improvement. Don’t believe you’re infallible. Writing is such a delicate, vulnerable craft, and it takes care and diligence and perseverance to find yourself, the stories you want to write, and how you want to write them.

Keep learning. Writing is the best form of evolution. Then reading. Then education, such as workshops or courses. But be open.

Always look for ways to develop.

Always find a way to work on your filter.

How I Used the Busybird Creative Fellowship: Maryanne Eve

November 9, 2017

This year I was the lucky recipient of the 2017 Busybird Publishing Creative Fellowship.

As an aspiring writer, I love to write, although all I’ve had published is a handful of articles for a sporting magazine years ago. I’m most certainly a complete novice, so I was overwhelmed and so very grateful to be awarded this honour.

It has been a fantastic experience, where I have learned a lot both formally and informally from the team at Busybird. Over the last twelve months my confidence and skills as a writer have increased and I have made some wonderful new networks and friends.

A big part of the fellowship has been having the assistance and support of Busybird writer, co-owner and publisher Blaise Van Hecke. Blaise has been a brilliant mentor and support throughout the last twelve months. She has spent sessions with me brainstorming and assisting me to make sense of my writing and the story I have been constructing.

My project is a collection of stories and experiences of women (including my own) and their recovery post Black Saturday Fires. At times, it has been challenging to pull it all together, due in part to the sensitivity of the subject material and also as I am relying on others to tell their story. Blaise really helped me through some of these obstacles, encouraging me to persevere, brainstorming, and helping me to think laterally.

From the very beginning I wanted this project to have meaning. As a social worker and survivor of Black Saturday, I really wanted to share the stories of survival, recovery and resilience and to help others who may be struggling with some sort of adversity. Blaise has at all times been encouraging and nurturing, and I have really appreciated her sharing her wealth of knowledge and experience with me. Through this process we have become good friends and shared many laughs and stories.

As part of the fellowship I was also fortunate to have the opportunity to attend a number of very helpful workshops on developing writing skills, editing and publishing. I really enjoyed these events and learned a lot, with my favourite being Book Camp. It was also an opportunity to meet and network with other writers. It was interesting and insightful to learn from others and to hear about their writing projects.

A big thanks to Blaise and the team at Busybird. It was a pleasure to attend the Busybird Publishing space, where I was always welcomed, supported and encouraged. I look forward to not only seeing my writing come to fruition and having my book published in the not too distant future, but also to the continued friendships.

The winner of the 2018 Busybird Creative Fellowship will be announced at the Busybird Christmas Party/Open Mic Nic 50, held on Wednesday, November, beginning from 6.00pm.